A tiny organism in the ocean might hold the key to solving one of our biggest environmental crises.

Scientists have discovered a marine bacterium with an extraordinary appetite: it actually breaks down and consumes plastic. This microscopic organism, found thriving in ocean waters, represents a potential breakthrough in addressing the massive problem of plastic pollution choking our seas.

The discovery offers genuine hope for tackling the millions of tons of plastic waste accumulating in marine environments worldwide.

1. This bacterium was discovered feeding on plastic debris in the Pacific Ocean.

Researchers stumbled upon this remarkable microorganism while studying plastic waste floating in Pacific waters. The bacterium, identified through genetic analysis, appears to have evolved the ability to metabolize polyethylene terephthalate (PET), the plastic commonly used in bottles and packaging. What makes this finding particularly exciting is that the organism was actively thriving on plastic particles, not just tolerating their presence.

The discovery happened during routine sampling of ocean microbiomes, when scientists noticed unusual bacterial activity around plastic fragments. Unlike previous lab-created enzymes that can break down plastic under specific conditions, this bacterium performs its plastic-eating feat in natural ocean temperatures and conditions, making it far more practical for real-world applications.

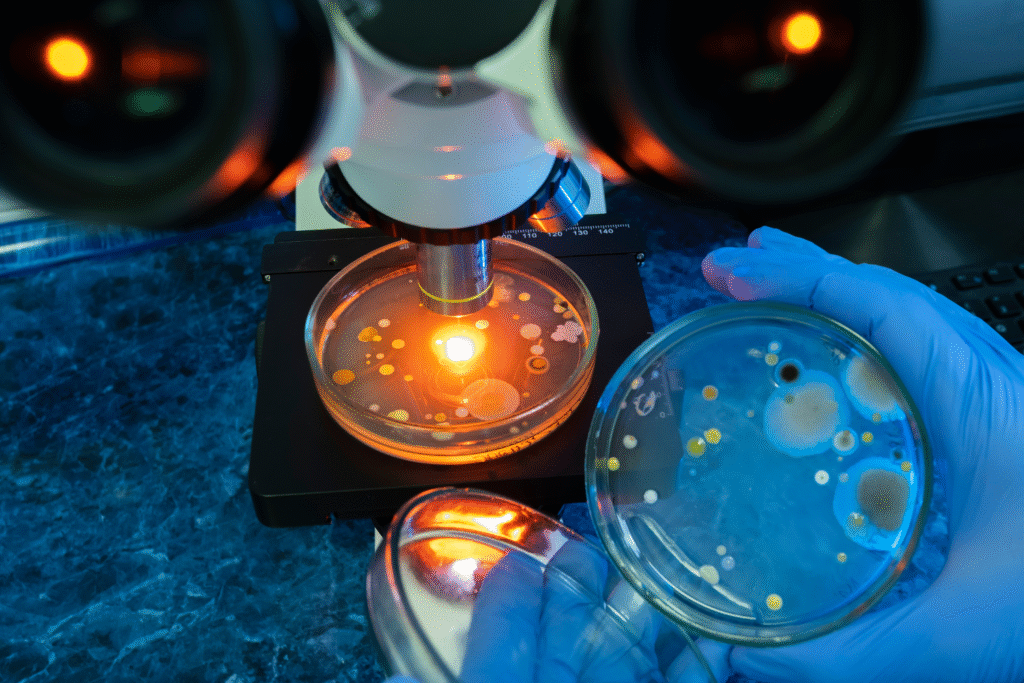

2. The bacteria produces specialized enzymes that break plastic into harmless compounds.

This ocean-dwelling bacterium secretes a unique combination of enzymes that can cleave the molecular bonds holding plastic polymers together. The process essentially reverses plastic manufacturing, breaking down complex chains into simple molecules the bacteria can absorb as nutrients. Scientists have identified the specific enzymes responsible and found they work remarkably efficiently compared to anything previously discovered.

The breakdown products are simple carbon compounds that other marine organisms can use, meaning the plastic doesn’t just disappear—it gets reintegrated into the ocean’s natural food web. This enzymatic process works at the cool temperatures typical of ocean water, which is crucial since most plastic-degrading enzymes only function in warmer laboratory settings.

3. Plastic pollution has reached catastrophic levels in our oceans.

Every year, approximately 8 million tons of plastic waste enters the world’s oceans, creating floating garbage patches and threatening marine life. Plastic debris has been found everywhere from surface waters to the deepest ocean trenches, and microplastics now contaminate the entire marine food chain. Sea turtles mistake plastic bags for jellyfish, seabirds feed plastic fragments to their chicks, and whales have died with stomachs full of plastic waste.

The persistence of plastic makes this pollution particularly devastating—conventional plastics can take hundreds of years to naturally degrade. Current cleanup efforts barely make a dent in the problem, removing only a tiny fraction of the plastic already in the oceans while millions more tons get added annually.

4. Scientists are now racing to understand and potentially harness this bacterial capability.

Research teams worldwide have begun studying this bacterium’s genetic blueprint to understand exactly how it evolved its plastic-eating abilities. The goal is to determine whether these microorganisms could be cultivated and deployed on a larger scale to help clean up ocean plastic pollution. Scientists are also investigating whether the plastic-degrading genes could be transferred to other bacteria that grow faster or thrive in different marine environments.

Initial experiments show promising results, with the bacteria successfully breaking down various types of plastic under controlled conditions. However, researchers emphasize that much work remains before this discovery can become a practical pollution solution. They need to ensure the bacteria won’t disrupt ocean ecosystems and that scaling up their plastic-eating activity is actually feasible.

5. This discovery joins other recent breakthroughs in biological plastic degradation.

Several years ago, Japanese researchers discovered a bacterium in recycling facilities that could degrade PET plastic, sparking worldwide interest in biological solutions to plastic waste. More recently, scientists have engineered enzymes that can break down plastic bottles in hours rather than centuries. Waxworms and mealworms have also demonstrated the ability to digest certain plastics, pointing to various biological pathways that nature has developed.

This new ocean bacterium adds to our growing toolkit of biological plastic fighters, but it’s particularly valuable because it operates in the marine environment where so much plastic accumulates. Each discovery builds our understanding of how life adapts to human-made materials and offers potential strategies for addressing pollution.

6. The bacteria’s discovery highlights nature’s remarkable ability to adapt to human pollution.

Evolution doesn’t wait for perfect conditions—organisms constantly adapt to whatever environment they encounter, including ones we’ve polluted. This bacterium likely developed its plastic-eating capability relatively recently, as widespread plastic pollution only became significant in the last several decades. The rapid adaptation demonstrates how microbial life can evolve solutions to entirely novel challenges within remarkably short timeframes.

Similar adaptations have been observed with bacteria learning to break down pesticides, industrial chemicals, and other synthetic compounds. Nature’s ability to develop biological responses to human pollution gives researchers hope that we might find or cultivate organisms to help remediate various types of environmental contamination, not just plastic waste.

7. Implementing this discovery as a real solution faces significant practical challenges.

Scaling up bacterial plastic degradation from laboratory samples to ocean-wide application involves enormous hurdles. Scientists need to cultivate massive quantities of bacteria, deliver them to polluted areas, and ensure they survive and function in diverse ocean conditions. There are also legitimate concerns about introducing large populations of any organism into marine ecosystems, even naturally occurring ones, without fully understanding the consequences.

The bacteria also work relatively slowly compared to the rate at which we’re adding new plastic to the oceans. Even if deployment proves successful, it won’t eliminate the need to dramatically reduce plastic production and improve waste management on land. This biological solution might help address existing pollution, but preventing future contamination remains the most critical priority.

8. The discovery could inspire new industrial applications beyond ocean cleanup.

Understanding how this bacterium breaks down plastic might lead to improvements in recycling technology and waste management facilities. Researchers are exploring whether the bacterial enzymes could be harvested and used in industrial processes to break down plastic waste more efficiently than current mechanical or chemical recycling methods. This could make recycling more economically viable and help reduce the amount of plastic ending up in landfills or oceans.

Some scientists envision bioreactors where these bacteria or their enzymes process plastic waste, converting it back into raw materials for manufacturing new products. This circular approach would keep plastic in the production cycle rather than allowing it to become pollution, fundamentally changing how we handle plastic waste management.