Hidden layers of text are rewriting what scholars thought they knew about ancient biblical manuscripts.

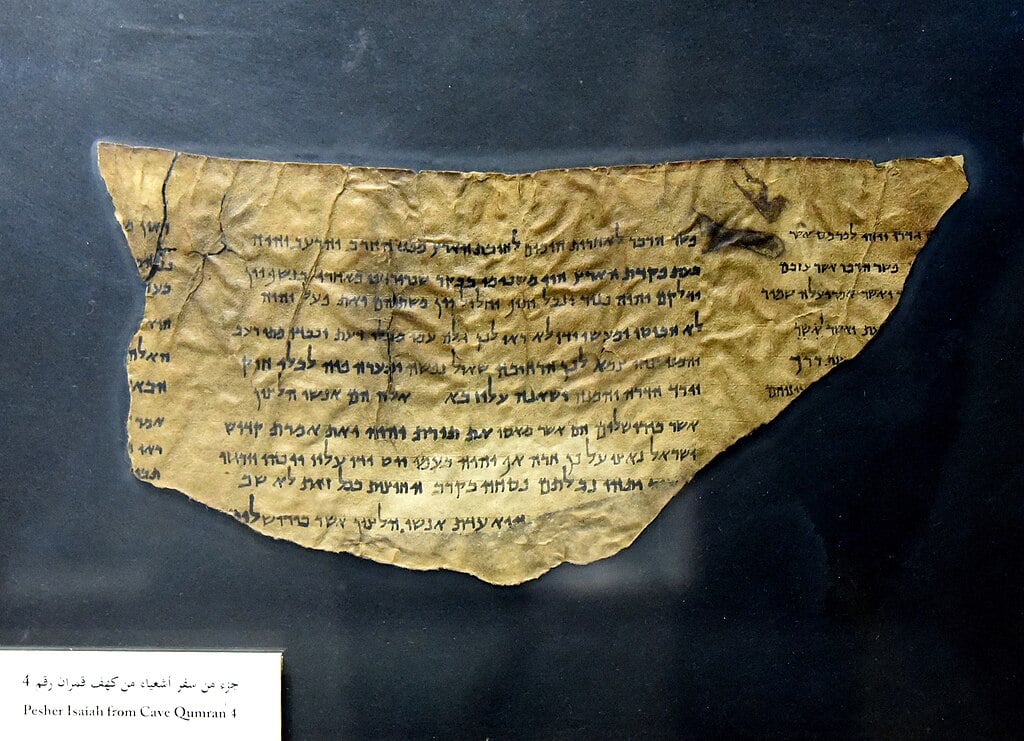

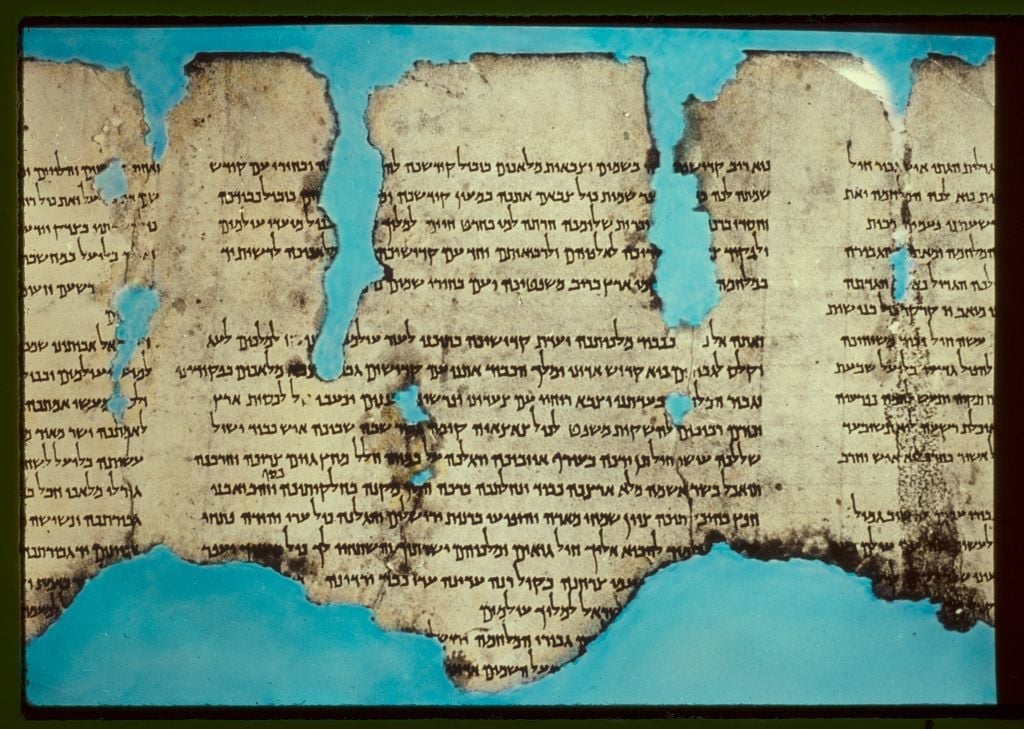

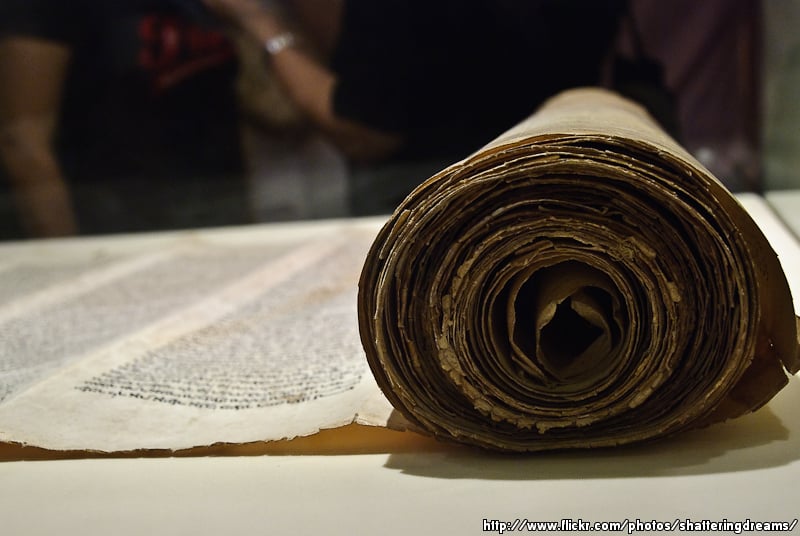

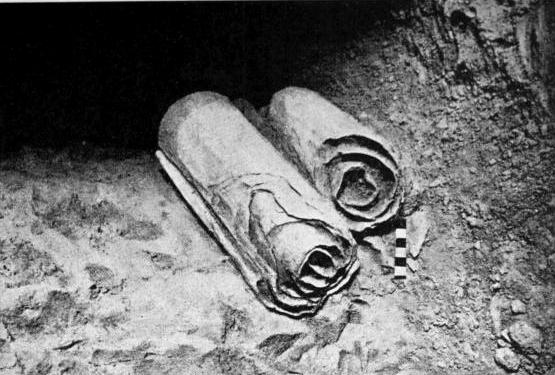

Advanced imaging technology has revealed previously invisible writing on fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls that researchers initially believed were blank or too damaged to read. These discoveries include marginalia, corrections, and entirely separate texts written in different hands, suggesting a far more complex transmission history than scholars previously understood. The implications extend beyond academic curiosity into fundamental questions about biblical authenticity and interpretation.

Each new discovery forces experts to reconsider long-held assumptions about how these ancient documents were created, copied, and preserved. The hidden scripts challenge traditional narratives about textual stability and raise profound questions about which versions of biblical texts should be considered authoritative.

1. Multispectral imaging reveals entire passages written between the lines of existing scrolls.

Researchers using advanced infrared and ultraviolet imaging have discovered that scribes often added text in spaces between original lines, creating layered manuscripts that previous generations of scholars never knew existed. These interlinear additions sometimes clarify ambiguous passages, but other times they introduce contradictory interpretations or entirely new theological concepts. The hidden text appears in different ink compositions and handwriting styles, indicating multiple scribes worked on single documents across different time periods.

Some interlinear passages appear to be alternative translations or interpretations that scribes wanted to preserve without erasing the original text. Others look like corrections or updates that later communities felt necessary to incorporate. The practice reveals that ancient Jewish communities viewed these texts as living documents subject to ongoing revision rather than frozen artifacts. This discovery fundamentally challenges the assumption that biblical manuscripts were copied with rigid precision and never altered.

2. Previously blank fragments actually contain entire psalms and prayers unknown to modern scholarship.

What researchers dismissed as blank parchment or too faded to read has yielded complete texts under multispectral analysis, including prayers and psalm variations that don’t appear in any canonical biblical collection. These discoveries expand the known corpus of ancient Jewish liturgical material and suggest that worship practices were far more diverse than surviving texts indicated. Some newly revealed prayers contain theological ideas that later religious authorities would have considered controversial or heretical.

The recovered texts include versions of familiar psalms with significant variations in wording and additional verses absent from traditional biblical manuscripts. Scholars now realize that standardization of biblical texts occurred much later than previously thought, and that early Jewish communities used multiple versions simultaneously without considering any single version definitive. These alternative psalms might have been deliberately hidden or allowed to fade as certain versions gained authority. Their recovery forces biblical scholars to acknowledge that substantial portions of ancient religious literature were lost, suppressed, or simply fell out of use, leaving an incomplete picture of early Jewish and Christian thought.

3. Secret marginalia contains commentary suggesting ancient scribes questioned certain biblical passages.

Tiny notations discovered along the edges of scroll fragments reveal that ancient copyists sometimes expressed doubts about the accuracy or interpretation of texts they were transcribing. These marginal notes include questioning marks, alternative word choices, and brief comments that suggest theological uncertainty or disagreement. The discovery humanizes the scribes and demonstrates that even in ancient times, religious scholars debated textual meanings and authenticity.

Some marginal notes reference other now-lost texts or traditions that apparently contradicted the versions being copied, indicating that scribes were aware of multiple conflicting accounts. Others appear to be personal reflections or warnings to future readers about problematic passages. This evidence contradicts the traditional view of ancient scribes as mechanical copyists who reproduced texts without critical engagement. Instead, these documents show intellectually active scholars who wrestled with the same textual problems that modern researchers encounter. The questioning marginalia suggests that claims of absolute biblical consistency or divine preservation of exact wording would have seemed naive even to the ancient communities who produced these scrolls.

4. Hidden texts reveal that some biblical books existed in radically different versions simultaneously.

Multispectral imaging has uncovered evidence that certain biblical books circulated in significantly divergent forms within the same communities and time periods. The Book of Jeremiah appears in versions that differ by entire chapters, with some containing prophecies and narratives completely absent from the traditional biblical text. Similarly, fragments of Exodus show variations in the Ten Commandments’ wording and order that challenge assumptions about textual uniformity.

These discoveries prove that the concept of a single authoritative version of biblical books is a relatively modern construct imposed retrospectively on ancient texts. Communities apparently accepted multiple versions as equally valid, using different manuscripts for different purposes or occasions. Some variations reflect theological evolution as Jewish thought developed over centuries. The hidden texts demonstrate that decisions about which versions became canonical were human choices made by religious authorities, not inevitable outcomes. Understanding that beloved biblical passages could have been entirely different had other manuscript traditions prevailed forces uncomfortable questions about the nature of scriptural authority.

5. Cryptic codes and ciphers embedded in scroll margins suggest esoteric knowledge transmission.

Researchers have identified systematic patterns of dots, marks, and letter substitutions in scroll margins that appear to encode information using ancient cryptographic techniques. These codes may have marked passages considered particularly sacred or dangerous, or they might have served as memory aids for oral traditions that accompanied written texts. Some patterns match known ancient cipher systems, while others remain undeciphered puzzles that could contain lost wisdom or simply mundane scribal notes.

The presence of deliberate encoding suggests that not all knowledge was meant to be accessible to every reader, contradicting modern assumptions about religious texts as democratically available. Certain teachings or interpretations may have been restricted to initiated members of specific groups. The codes might reference mystical traditions, calendrical calculations, or prophetic interpretations that the broader community wasn’t supposed to access. Their discovery validates historical accounts of esoteric Jewish traditions that mainstream scholarship often dismissed as later inventions. The inability to decode some of these systems means crucial context for understanding biblical passages may remain permanently lost.

6. Newly visible corrections show scribes deliberately changed texts to support evolving theological positions.

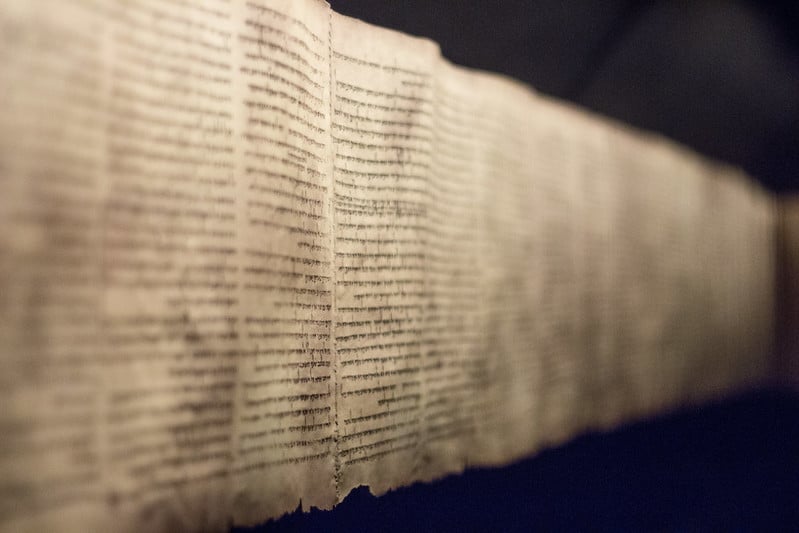

Analysis of visible alterations under advanced imaging reveals that copyists sometimes systematically modified passages to align with changing religious views, erasing original words and substituting text that better supported contemporary beliefs. These weren’t accidental errors but intentional revisions that removed problematic content or inserted theologically preferable language. Some changes appear coordinated across multiple manuscripts, suggesting organized efforts to revise texts.

Particularly striking are modifications that softened references to multiple deities or removed passages suggesting God had a physical form, changes that align with later monotheistic orthodoxy but contradict earlier Israelite religious practices. Other alterations seem designed to increase emphasis on specific laws or de-emphasize passages that later communities found embarrassing. The systematic nature of these changes demonstrates that biblical texts underwent deliberate editing to serve religious and political agendas. This evidence makes it impossible to claim that modern Bibles contain exactly what original authors wrote. Every biblical text available today represents choices made by numerous individuals across centuries about what to preserve, alter, or discard.

7. Hidden dating markers indicate some scrolls were created centuries later than experts believed.

Microscopic analysis of ink composition and previously invisible scribe marks has revealed that certain Dead Sea Scroll fragments date to significantly different periods than their handwriting styles suggested. Some texts attributed to the third century BCE based on paleographic analysis actually contain chemical signatures indicating first-century CE production. These misdatings affect scholarly understanding of when biblical books reached their current forms and how quickly religious ideas spread.

The dating revelations also expose limitations in traditional manuscript dating methods that relied heavily on handwriting analysis without chemical verification. Scribes apparently sometimes deliberately imitated archaic writing styles, perhaps to make newer texts appear more ancient and authoritative. Some fragments previously considered among the oldest witnesses to biblical texts now appear to be relatively late copies, forcing scholars to revise theories about textual development. The chronological confusion means that assumptions about which manuscript versions influenced others may be completely backwards. Reconstructing the actual evolution of biblical texts becomes vastly more complicated when documents can’t be reliably placed in historical sequence.

8. Recovered texts include references to biblical figures and events absent from canonical scriptures.

Hidden passages describe encounters, prophecies, and biographical details about major biblical characters that never made it into traditional biblical books. Some fragments expand the stories of Abraham, Moses, and David with additional adventures and teachings that provide very different characterizations than canonical accounts. Other newly visible texts reference prophets and leaders who apparently held significance in ancient communities but were completely forgotten by later traditions.

These lost narratives raise questions about why certain stories were preserved while others disappeared, and who made those selection decisions. Some recovered material contradicts or complicates canonical accounts, suggesting that early communities maintained diverse and sometimes conflicting traditions about their religious history. The rediscovered texts prove that the biblical narrative represents a curated selection from a much larger body of material rather than a comprehensive historical record. Modern readers encounter only the stories that survived multiple filtering processes by ancient editors, copyists, and religious authorities. The hidden scripts hint at richly complex traditions that were deliberately or accidentally erased, leaving the theological landscape significantly impoverished.