Scientists just uncovered something that challenges decades of carbon dating assumptions.

For years, the Shroud of Turin has sparked fierce debate between believers who see it as Christ’s burial cloth and skeptics who point to 1988 radiocarbon tests dating it to medieval times. That seemed to settle things—until now.

Recent research suggests those famous tests might have gotten it wrong, and the reasons why are forcing scientists to rethink what they thought they knew about this ancient relic.

1. The original carbon dating may have tested the wrong material entirely.

When scientists analyzed the shroud in 1988, they confidently dated it to between 1260 and 1390 AD, seemingly proving it was a medieval forgery. However, new research published in 2022 suggests the samples tested weren’t original shroud material at all. Using advanced imaging technology, Italian researcher Tristan Casabianca discovered that the tested corner had been rewoven during medieval repairs, mixing newer cotton threads with the original linen.

This revelation is massive because it means the landmark study that shaped public opinion for decades analyzed patch material rather than the authentic cloth. The implications extend beyond the shroud itself—it raises questions about how we approach artifact testing and whether other historical conclusions might need revisiting based on similar contamination issues.

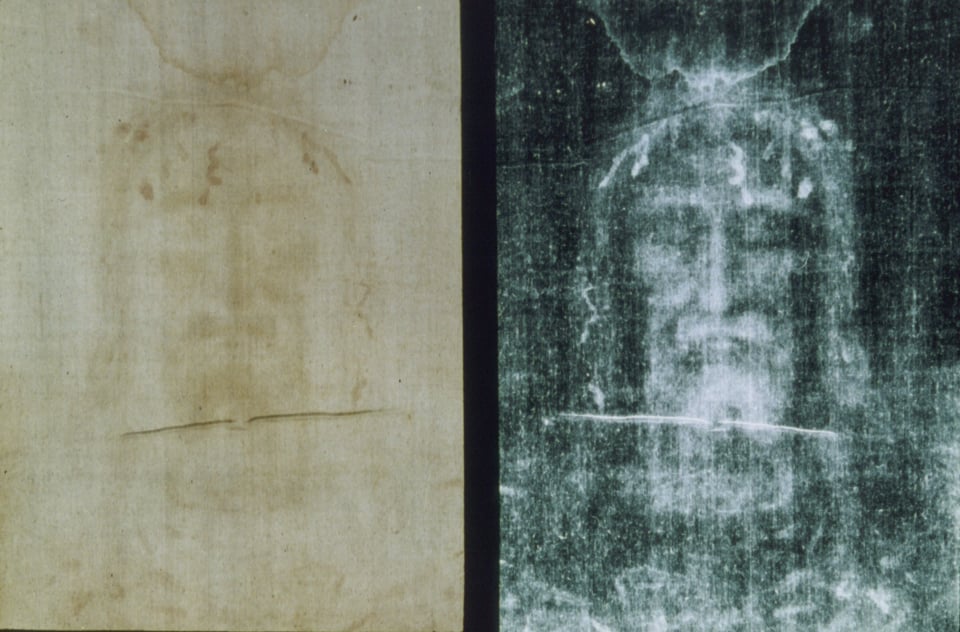

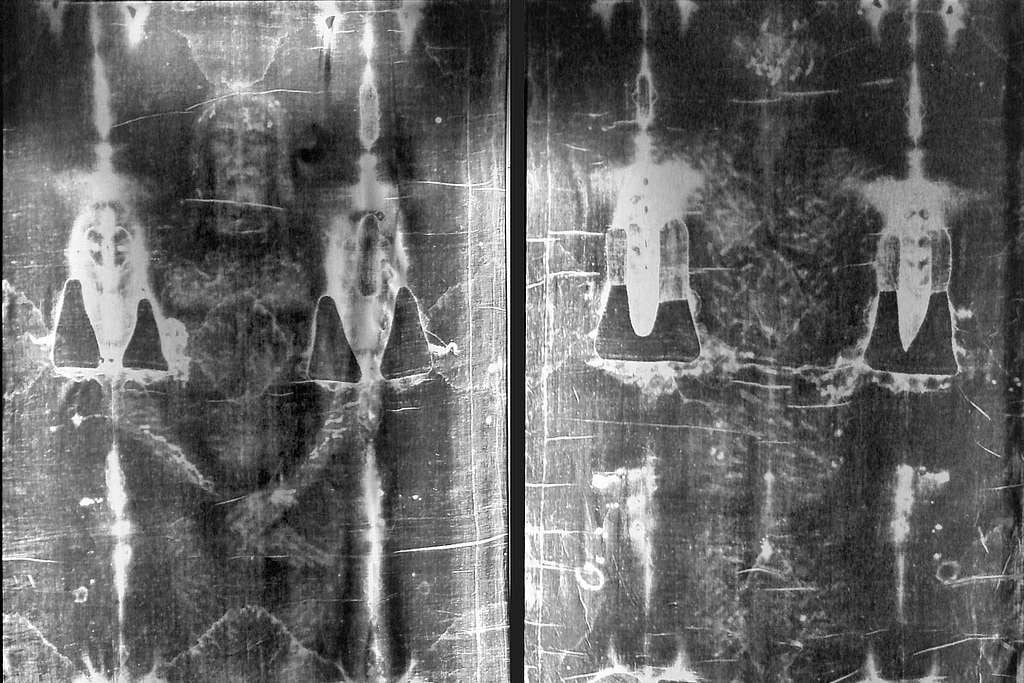

2. New X-ray technology reveals the linen could be 2,000 years old after all.

Italian scientists using wide-angle X-ray scattering examined the shroud’s cellulose structure and found aging patterns consistent with first-century linen. This 2022 study analyzed how the fabric’s molecular structure breaks down over time, comparing it with other dated linens from various periods. The results placed the shroud squarely in the time of Christ, directly contradicting the 1988 findings.

What makes this approach compelling is that it doesn’t rely on carbon dating at all, which can be contaminated by handling, fires, or environmental factors. Instead, it measures the natural deterioration of the fabric’s fibers themselves. The research team emphasized they weren’t trying to prove religious authenticity but simply determining the cloth’s actual age using modern materials science.

3. The image formation remains unexplainable by any known medieval technique.

Perhaps the most puzzling aspect isn’t the dating controversy but how the image got there in the first place. Studies show the brown discoloration creating the figure penetrates only the top two microfibers of each thread—about one-fifth the diameter of a human hair. No paint, dye, or pigment has been found, and the image contains three-dimensional information that wouldn’t be encoded by any artist working in the 1300s.

Scientists have attempted to recreate it using every method available to medieval forgers—painting, scorching, acid staining, bas-relief techniques—yet none produce the shroud’s unique characteristics. Even more baffling, the image is essentially a photographic negative, a concept unknown until the 1800s. The formation process remains one of forensic science’s genuine mysteries that continues to baffle researchers today.

4. Pollen and dust particles point to a Jerusalem origin.

Botanical evidence strengthens the case for the shroud’s ancient Middle Eastern origins. Max Frei, a Swiss criminologist, identified pollen from 58 plant species on the cloth, with many exclusive to Palestine and the Dead Sea region. Some of these plants bloom only in March and April—precisely when the Gospels place Christ’s crucifixion.

Additionally, dust particles embedded in the fabric match the unique limestone composition found in Jerusalem tomb caves. This geological fingerprinting is extremely difficult to fake, especially in medieval Europe where forgers would have no access to such specific materials or knowledge of their significance. The microscopic evidence suggests the cloth was in Jerusalem at some point, regardless of when it was created.

5. Blood stains show patterns consistent with crucifixion wounds.

Forensic pathologist Robert Bucklin analyzed the blood patterns and found them consistent with wounds from crucifixion, including flows from the wrists rather than palms—anatomically correct but contrary to medieval artistic convention. The stains contain real human blood with components of type AB, and serum halos surround the blood marks, indicating genuine clotting patterns that would be nearly impossible for a medieval artist to replicate convincingly.

What’s particularly interesting is that the blood transferred to the cloth before the mysterious image formed, suggesting two separate processes occurred. Chemical analysis reveals elevated bilirubin levels in the blood, consistent with someone who died under severe trauma. These forensic details align with crucifixion accounts but would require impossibly sophisticated medical knowledge for a medieval forger to fabricate accurately.

6. The 1532 fire should have destroyed any medieval forgery.

In 1532, a fire in the Sainte-Chapelle in Chambéry nearly destroyed the shroud, with molten silver burning through the folded cloth. If the image had been created with any known medieval substance—paint, dye, or pigment—the intense heat should have drastically altered or destroyed it. Yet the image remained essentially unchanged, aside from the scorch marks and water stains from extinguishing the fire.

Modern testing shows that temperatures sufficient to melt silver would vaporize or fundamentally change any organic artistic materials from that era. The image’s survival suggests it wasn’t created through conventional means. This accidental experiment actually strengthens arguments for the cloth’s authenticity, since whatever created the image demonstrated remarkable thermal stability that medieval materials simply don’t possess.

7. Historical records may trace the shroud back centuries before the Middle Ages.

While skeptics note the shroud’s first definitive appearance in historical records was 1350s France, researchers have identified potential earlier references. The Image of Edessa, a legendary cloth bearing Christ’s face mentioned in Byzantine texts from the 6th century, shares striking similarities with the shroud. Some historians believe they’re the same artifact, with the shroud folded to display only the face during those centuries.

Ian Wilson’s research traces a possible route from Jerusalem to Constantinople to France, accounting for the apparent gap in documentation. Ancient records describe this sacred image as “acheiropoeitos”—not made by human hands—matching descriptions of the shroud. If this connection holds, the cloth’s history extends back much further than carbon dating suggested, potentially reaching apostolic times.

8. Modern AI analysis detects details invisible to medieval artists.

Recent artificial intelligence studies of high-resolution shroud images have identified details that wouldn’t be visible to the naked eye, including coin impressions over the eyes matching lepton coins minted under Pontius Pilate. These findings, while controversial, suggest information encoded in the image that a medieval forger couldn’t have intentionally included because they couldn’t see these features themselves.

Computer analysis also revealed that the image’s contrast and shading contain distance information—the lighter areas correspond to cloth sections that would have been farther from a body. This three-dimensional encoding allows researchers to create accurate sculptural recreations of the figure. Such sophisticated spatial data embedded in a flat image seems impossibly advanced for medieval technology or artistic technique.