Ancient footprints preserved in dried lakebed mud are rewriting the entire timeline of human arrival in America.

Researchers discovered thousands of fossilized human footprints at White Sands National Park in New Mexico, dated to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago. This discovery pushes back the established timeline of human presence in North America by at least 7,000 years, fundamentally challenging what archaeologists thought they knew about migration patterns.

The prints reveal detailed snapshots of daily life during the last Ice Age, showing adults, teenagers, and children walking across mudflats that are now desert.

1. The footprints were preserved in layers of sediment at an ancient lakebed.

White Sands contains exceptional fossil beds where human tracks were embedded in soft mud, then covered by subsequent layers of sediment that hardened over millennia. The prints remained remarkably intact because the lakebed environment provided ideal preservation conditions—wet enough to capture fine details like toe impressions, then dry enough to solidify before erosion could destroy them. Scientists found thousands of individual footprints spread across multiple layers representing different time periods.

The sediment layers containing the prints also held seeds from aquatic plants that researchers used for radiocarbon dating, providing reliable age estimates. These seeds grew in the exact same mud that preserved the footprints, eliminating questions about whether the dates accurately reflect when people walked there. The geological context proves humans were definitely walking around New Mexico during the height of the last Ice Age. This timing contradicts the long-held Clovis-first theory that dominated American archaeology for decades.

2. Previous archaeological consensus held that humans arrived in America around 13,000 years ago.

The Clovis culture, named after distinctive spear points first found near Clovis, New Mexico, was long considered the earliest human presence in the Americas. This theory suggested people crossed the Bering land bridge around 13,000 years ago when glaciers retreated enough to open an ice-free corridor through Canada. Generations of archaeologists built their understanding of American prehistory around this framework, and any claims of earlier dates faced intense skepticism.

Pre-Clovis sites have occasionally been proposed over the years, but most faced criticism about dating methods, contamination issues, or whether artifacts were genuinely human-made. The White Sands footprints provide such unambiguous evidence that even skeptics acknowledge they’ve fundamentally changed the conversation.

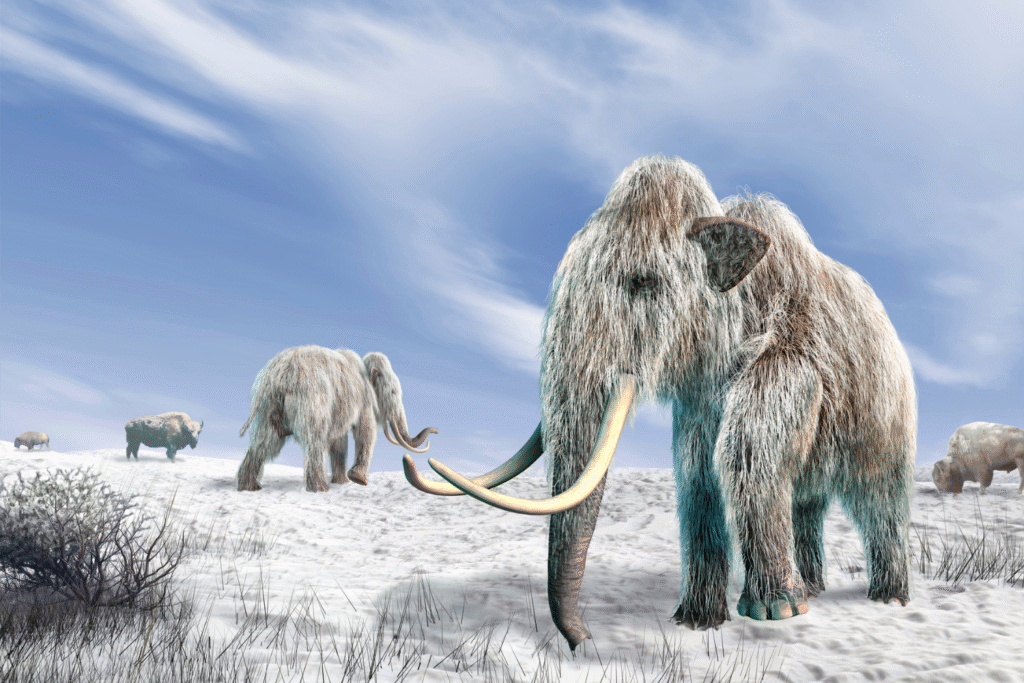

3. The footprints show that people coexisted with now-extinct Ice Age megafauna.

Tracks of giant ground sloths, mammoths, and other extinct animals appear in the same sediment layers as human footprints, providing direct evidence of humans living alongside these creatures. Some prints show intriguing interactions—human tracks approaching or following animal trails, suggesting hunting or tracking behavior. In several instances, researchers found evidence that humans deliberately stepped in fresh animal tracks, possibly to mask their presence or study the animals.

This coexistence raises fascinating questions about how these early Americans interacted with megafauna and whether human hunting contributed to their eventual extinction. The footprints capture moments of daily life frozen in time: children playing near the water’s edge while adults worked, teenagers apparently running, and what looks like someone carrying a small child.

4. The discovery challenges theories about migration routes into the Americas.

If humans were in New Mexico 23,000 years ago, they couldn’t have used the ice-free corridor through Canada that supposedly opened around 13,000 years ago. The massive Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets completely blocked interior routes during the time these footprints were made. This timing strongly supports the coastal migration theory—the idea that people traveled down the Pacific coast by boat, following the shoreline and living off marine resources.

A coastal route would have remained accessible even during maximum glaciation since ocean travel doesn’t require ice-free land corridors. Archaeological evidence for this coastal migration is scarce because Ice Age coastlines now lie underwater after sea levels rose when glaciers melted. The White Sands footprints provide inland evidence that people were definitely here during a time when coastal migration was the only plausible route.

5. Dating methods used multiple independent techniques to confirm the ancient age.

Researchers employed radiocarbon dating on aquatic plant seeds found in the same sediment layers as the footprints, providing direct age estimates. They also used optically stimulated luminescence dating on quartz grains to determine when sediments were last exposed to sunlight. Both methods produced consistent results pointing to the 21,000-23,000 year range, eliminating concerns about contamination or methodological errors that have plagued other pre-Clovis claims.

Critics have largely accepted these dates because the evidence meets the highest standards of archaeological science, something previous pre-Clovis sites often couldn’t claim convincingly enough to overcome entrenched skepticism.

6. The footprints reveal surprising details about the people who made them.

Researchers can determine approximate age and size of individuals based on footprint dimensions and depth, revealing that groups included children, teenagers, and adults. Some prints show clear toe impressions indicating people walked barefoot despite the muddy conditions. The stride patterns and track distributions suggest people weren’t just passing through but engaged in various activities around the lakeshore—playing, working, and traveling in different directions.

Certain trackways show what appear to be adults carrying young children, as evidenced by deeper, unevenly spaced impressions suggesting extra weight. Clusters of small footprints suggest children playing or working together near the water’s edge.

7. Climate conditions during the Ice Age made the American Southwest surprisingly habitable.

During the last glacial maximum, New Mexico’s climate was cooler and much wetter than today’s desert conditions. The ancient Lake Otero covered hundreds of square miles where White Sands National Park now sits, providing abundant water and supporting diverse plant and animal communities. Grasslands and wetlands flourished in areas that are currently barren, creating productive environments capable of supporting human populations year-round.

These favorable conditions explain why people would occupy interior North America rather than staying near coasts where they presumably first arrived. The region offered reliable water sources, large game animals attracted to the lake, and edible plants in surrounding grasslands. Humans clearly recognized the area’s value and returned repeatedly over thousands of years based on footprint evidence spanning multiple time periods.

8. The discovery has sparked renewed interest in finding additional pre-Clovis sites.

Archaeologists are reexamining previously dismissed sites and dating methods with fresh perspectives now that the 23,000-year timeline has been established. Several locations that produced controversial dates in the past are receiving serious reconsideration as the field acknowledges that earlier human presence is not just possible but proven. Funding has increased for research targeting older sites and underwater archaeology along ancient coastlines.

The field of American archaeology is experiencing a paradigm shift comparable to when the Clovis-first model initially became accepted, except this time the timeline is extending dramatically deeper into the past. We’re likely on the verge of multiple new discoveries that will continue reshaping our understanding of when and how humans first populated the Americas.